FEBRUARY 2026

.jpeg)

Irene Vines

Louisiana Champion

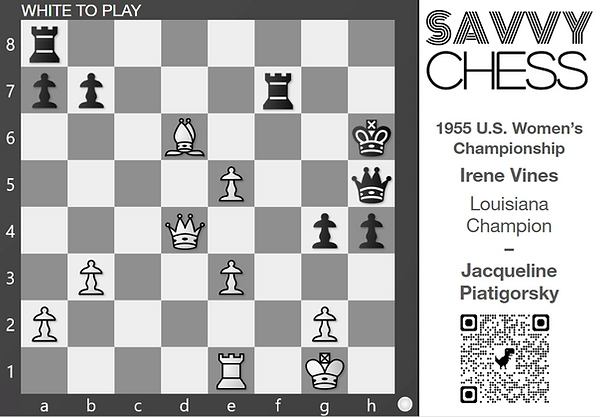

The 1955 U.S. Women’s Chess Championship was held in New York, and attracted female players from across the country to face off in a round robin format to become the next U.S. Women’s Champion. Louisiana Champion Irene Vines (White) travelled from her native New Orleans for the occasion and in this game faced off against Jacqueline Piatigorsky (Black), who frequented national chess events and was well-known as a patron of the arts, giving an endowment to the New England Conservatory of Music and sponsoring the famous 1961 chess match, Bobby Fischer vs. Reshevsky. Fame has little benefit on the chessboard, and Vines seized a brief chance to win in this position. Piatigorsky had just missed an opportunity to open up the position of White’s king with a timely …h3! break, with the idea to trade the pawns and attack the king openly–so Vines returned the favor in the diagram position.

Superficially, one might expect that White has a disadvantage due to the imbalance of a bishop against a rook. In most positions, the rook outshines the bishop due to its ability to control both colors in additional to the long range power that it shares with the bishop. For that reason, White has to play energetically to keep their bishop stronger than the rook on a8, which is temporarily out of play, and to make use of Black’s disadvantages. The black king is weak since all the pawns near the king have advanced or been exchanged. White’s king is not much better, and if White does not seize the initiative, in the next few moves Black will play …h3, …hxg2, and attack the king openly. Therefore White played 1.e6!, attacking the rook, taking a step towards promoting the e-pawn to a stronger piece by reaching e8, and opening dark square diagonals for the bishop and queen to pursue the enemy king. Black’s options are limited–simply going ahead and ignoring the hanging rook on f7 is too slow, so that leaves only 1…Rf5, 1…Rg7, and 1…Rh7 as serious candidates (other moves result in the rook being captured). Even though Black has a rook for a bishop (an “exchange”), trading rook for bishop to make it materially even again doesn’t help because of the advanced e-pawn and weak king–White’s initiative continues. Each defensive option has its inadequacies, but they can be summarized with the same attacking concept for White: bring the rest of the pieces including the rook to attack the king.

After 1…Rh7, Black loses dramatically. 2.Qf6+ Qg7 (this is Black’s only move to block check) 3.Bf4+ Kh5 (only king move) 4.Qe5+ Qg5 (only way to block check) 5.Qxg5# ends the game immediately, win for White, no alternatives for Black along the way. 1…Rg7 instead loses to 2.Rf1! Activating the last piece that isn’t ready to attack the king. This immediately threatens 3.Bf8, pinning the rook to the king, so Black should answer 2.Rf1 with 2…Kh7, but Black is clearly backpedaling. White can continue 3.Be5! utilizing the square vacated when the pawn advanced to e6. After 3…Re7, it’s dealer’s choice with multiple avenues to win–pick your favorite between 4.Qe4+ and 4.Rf6 for instance, they can run all the want but with the rook on a8 out of play, they can’t hide from the bishop, pawn, rook, and queen. Playing out different ways the game could end from here could be an amusing exercise–who doesn’t enjoy enumerating all the ways they are winning? If Black tries the last resort, 1…Rf5, there are again multiple ways to win, but the simplest is probably what Vines played in the game. The game continuation was 1…Rf5 2.Bf4+ (2.e4! was another interesting option similar to the response to 1…Rg7–once the rook on f5 runs from the pawn, White takes over with Rf1) 2…Kg6 (2…Kh7 again White can play a thematic transfer of the rook, but this time not on f1: 3.Rc1!) 3.Qd7 (trapping the king on the sixth rank and preparing to advance the pawn) 3…Qh7 4.e7 Qf7 (resisting e8=Q by guarding e8 with queen and rook) 5.Qd8! and if the queen is taken, the pawn promotes to a new queen, effectively trading a pawn for a rook. With such a dominant position, Black can only hang on while White improves every piece, threatening to promote and simultaneously attacking the king.

The game continued 5…Qe8 6.Rd1, at which point Black finally cracked under pressure with the blunder 6…Rc5?. This is a good moment to set up the position and look for a one-move opportunity for White to either checkmate or win material. White found the best move: 7.Qd6+! attacking the king and unprotected rook simultaneously. Black played a few more moves before the bishop and queen hunted the king down on the dark squares. 7…Kf7 8.Qxc5 Rc8 9.Qf5+ Kg8 10.Qe6+ Kh7 11.Qh6+ Kg8 12.Be5 with checkmate coming after 12…Qf7 (to protect g7) 13.Qh8#. The finish in this game may seem complex because of the several options that need to be considered at each step of the way, and the variations that can be a few moves long. It’s easy to imagine Vines and Piatigorsky visualizing the board each in their mind’s eye, running through intricate attacks and defenses. However, each move is united by a common concept: in order to preserve the attack on the king, every move must create immediate problems for the opponent, and all pieces should coordinate together in the attack.

The SavvyChess team verified that Irene Vines was the 1955 Louisiana Chess Champion, contrary to an article by ChessBase, by consulting six-time Louisiana champion James Rouselle and the Historic New Orleans Collection.

FIDE Master

Nicholas Matta

JANUARY 2026

FIDE Master

Nicholas Matta

FIDE Master (FM) Nicholas Matta (White) is a New Orleans native and the current Louisiana Chess Champion. Grandmaster (GM) Jacek Stopa (Black) is from Poland and has won numerous international tournaments, and was even the 2005 European junior champion of solving composed chess problems. In the diagram position, it is easy to imagine that Black could be winning on the basis that they have a rook against a bishop. In most positions the rook is stronger, earning it a nominal value around five pawns, whereas the bishop is often considered around three pawns in value. However, this position is an exception. In positions where the two bishops have room to maneuver and attack weaknesses–a situation often called having a “two bishops advantage”–they are stronger than normal and may dominate the rooks. The evidence for this is in the vulnerability of the knight to the light bishop and the control of squares near the king on both light and dark squares by the bishops.

To convert this to an advantage, many attacking options may come to mind. For example, doesn't 1.Rxe8+ Rxe8 2.Bxc6 win a piece? Unfortunately not, because Black has their own forcing move in the end: 2…Re6! attacking both bishops–and opposite color bishops can't directly protect each other. The direct 1.Bxc6 doesn't work either due to 1…Rxe2. Almost any move you consider might run into either a rook capture on the e-file, the knight escaping, or losing a bishop after initial gains. The key here is to imagine what would be required to win the game by checkmate, observing that the light bishop already controls squares near the king. To finish it off, you need control of the dark squares… which brings us to our winning move below. Take a moment to try it again with this additional hint if you want.

1.Bg5! is a multi-purpose move, attacking the rook on d8 but more importantly, threatening Bf6#, winning the game. Black has to prevent this but cannot do so without incurring a material loss such as giving up the knight. For instance, simply guarding f6 with a rook, 1…Rf8, will take the pressure off the rook on e2 and allows 2.Bxc6. Note that with the bishop on g5, there is no double attack on the two bishops possible. The trickiest way to proceed is to meet 1.Bg5 with 1…h6, a seemingly harmless move that makes a space for the king to run on h7. The trick is, Black is up an “exchange” (rook against minor piece–that is, a bishop or knight), so they want to entice White to take the rook, leaving things closer to equality. However, White can go for the full piece with 1.Rxe8+! Rxe8 2.Bxc6. The last wrinkle is to evaluate the final position correctly. With two bishops against an active rook that could invade via Re2, one might worry that it's not enough to win the game. Rest assured, the two bishops have lots of targets to attack–the pawns–and Black is far from creating a passed pawn that could run to the end and become a queen. White does have to take care to control that, as it is Black’s best bet, but also, White can do the same with the support of two bishops, perhaps forcing the f-pawn ahead to the end. This opportunity was missed in the game, which ultimately ended in a draw in time trouble complications. Nevertheless, in this event, Nicholas Matta attained his FIDE Master title from the International Chess Federation, Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE) in addition to the U.S. title of National Master that he previously held. A fine game between our state champion FM Nicholas Matta against a holder of the most prestigious title in chess, GM Jacek Stopa!

DECEMBER 2025

.jpg)

Chess Prodigy

Paul Morphy

Paul Morphy (playing White here) was a bit of a prodigy, and rose to chess fame while waiting to turn 18 so that he could practice law in his native New Orleans. Morphy is widely regarded as an early chess World Champion due to his unprecedented extreme accuracy and global victories. However, the first official World Championship title was only granted in 1886 to Wilhelm Steinitz from Kingdom of Bohemia (later, Austria), who strangely enough never got a chance to play Morphy despite his best efforts. James McConnell (playing Black), was a friend and punching bag of Morphy’s–a New Orleans lawyer and Tulane donor. In this position, one should look for a win.

It is natural to examine all checks and captures here, which will point out important features of the position. For instance, almost any check (except double check, which forces the king to move), gives Black a moment to capture the rook on g5 with the pawn, escaping check. Even the double check options–Bb4+ and Bb6+--are thwarted by Kxb4 and Kxb6 respectively. But the spirit of the attacks on the king is right. The king is in an unusual and unfavorable position (if you see the full game, it is instructive to see how Morphy drove the king there), and simple means of winning by brute force, like taking the rook on h8 with the knight, only simplify the position after …hxg5, the same as before. A different way of looking at the position helps to efficiently find the answer.

Examining the squares around the king, one can see a “mating net” or killbox, a set of squares that are already under control and restrict the king. To checkmate, you don’t just need to surround the king–it is necessary to attack the king, such that they cannot capture, block, or run away. Taking stock, a6 and b5 are controlled by the light bishop, and b6 and b4 are controlled by the dark bishop. The only squares we need to control to win the game are a5 and a4. Therefore, it helps to imagine… if you could pick up a piece and put it anywhere, what move would you play? Are any moves like that actually realistic? If you want a rook on a3, look and see how that can be achieved before reading the answer.

The rook on g5 can reach a3 via 1.Rg3! There is no move for Black that can prevent the move to follow or create space to run. McConnell tried 1…b5 but it’s no use, 2.Ra3# comes next. It’s a mate in two position, but chess is tricky and it can still take quite some effort to spot it. This thinking technique, imagining what is needed to finish the checkmate pattern, applies in many positions, and is a general skill. There is a chess proverb: “Chess is a sea in which a gnat may drink and an elephant may bathe”. The paradox of chess is what makes it fun and endless.

NOVEMBER 2025

.jpg)

Life Master

Alfred "Big Al" Carlin

Five-time Louisiana Champion Alfred Carlin was playing Black in this winning position. "Winning" doesn't necessarily mean "checkmating", although that would be nice of course. Winning move can also mean a move that creates an advantage that is great enough to reasonably win the game later on--such as by winning one or more pieces with some combination of checks, captures, and threats. (Colloquially, players often call everything except pawns "pieces"--because pawns are just that special.)

While looking at captures the weakness of the f2-square may stand out since it is attacked by the knight on h3 and defended only by the king. Additionally, the knight on f3 is under attack by the rook--the rook also attacks f2, and one could imagine that if the knight can be made to move, Rxf2 would be checkmate! This opens up possibilities one might ordinarily find repugnant and makes them enticing. The rook on b2 is also unprotected; this coincidence would suggest that ...Qd4 should win because it attacks the weakness on f2 and b2. A move like Ne5 or Nd4 lacks the force of attacking two weaknesses and is less logical. If White plays Nxd4, Rxf2# wins instantly. But your opponent also has a right to live and would play Rxe7+! creating a space for the king on e1 so that Rxf2 is not mate before playing Nxd4. But don't give up on the idea--just change the order of operations. After 1...Nxf2 2.Kxf2 Qd4+! White has no time for Rxe7 due to the check, and has to give up the rook for the sacrificed knight (the knight is pinned). White can avoid this, but only by giving up the pawn on f2 and leaving their king vulnerable.